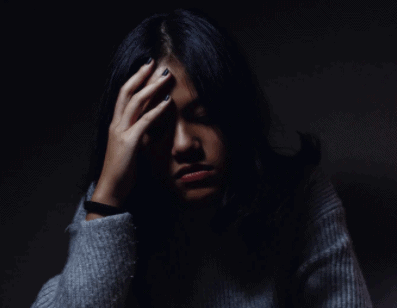

The pandemic has been devastating for mental health.

The isolation, health concerns, and unpredictability has meant that anxiety is on the rise for many of us. According to new findings by Mental Health Research Canada, 28 per cent of Canadians report high levels of anxiety and 17 per cent report high levels of depression. On top of that, one-third of Canadians report that their poor mental health affects their ability to function.

But even before the COVID-19 pandemic, women and gender-diverse people had significant mental health concerns. Women experience depression and anxiety twice as often as men but experience more barriers in getting care, and gender-diverse individuals face even higher rates of mental health difficulties compared to cisgender people.

In the pandemic, we’re seeing a unique toll on mothers and family caregivers. They are the backbone of much of the day-to-day pandemic response, carrying much of the housework and caregiving as before, with an additional load from schools and daycare closures. They have demonstrated incredible strength in the face of these challenges, balancing paid work, family and home needs, and community involvement, but these challenges have taken their toll.

The biggest difference in the data between mothers and fathers is the “anxiety scales”—the severity of self-reported anxiety by the two groups.

There’s a 45 per cent difference in the rates of high levels of depression between mothers and the general population. Similarly, in early December, the number of mothers reporting high anxiety was twice that of the rest of the respondents.

This data is consistent with earlier findings about women’s “worry work” in the pandemic. A study by Abacus Data in March 2020 indicated that women in Canada were significantly more worried about the COVID-19 crisis than men: 49 per cent of women reported feeling “very worried” about the outbreak, compared to 33 per cent of men. Thirty-seven per cent of men said they are “not worried at all” or “worried only a little”.

Women in heterosexual pairings have long taken the position of “designated worrier”. They tend to bear the brunt of the anxiety about family health and well-being. Of course, the data shows how worry work often comes at the expense of a mother’s own health and well-being.

In an April 2021 poll by the Canadian Women’s Foundation, almost half of mothers were “reaching their breaking point.” Our open-ended survey of mothers and family caregivers provides even more insight.

“The pandemic is making it even more impossible to be a caregiver to my three children and not miss time at work,” says one mother. “Losing pay that I can’t afford to lose, losing accountability with my employer, and losing confidence in my ability to be a provider.”

“I’m caring for my children and parents while trying to keep myself healthy and well,” says another. “I also have responsibilities to my employer. It’s been trial by fire. I have had many break downs and cried more in this year than ever.”

As of late, there has been more conversation on what mothers go through. What we need to do to take action and make things better for all mothers and family caregivers, particularly those who are most marginalized, revolves around policy change as well as our own behaviors.

Fathers and other family members need to take on an equitable amount of caregiving and housework, including raising children and looking after elders. The division of labour must be split in such a way that mothers can make their own mental health a priority. Their role is so important in families and communities. Their well-being enhances everyone’s well-being.

Workplaces also need to provide support to mothers and family caregivers as they contribute to the labour force. This includes childcare supports and sick days. It also includes breaking barriers to their advancement. Employers must critically consider how their workplace policies and practices impact mothers with a “motherhood penalty” and place other obstacles in their path.

And legislation, public policy, and governmental initiatives must respond to the complex realities faced by diverse mothers and family caregivers. An affordable national childcare plan is an excellent start, but it’s just the beginning. The reality is that we all need to look to our own lives and our collective families and communities to prioritize supporting mothers and family caregivers who are struggling right now.

Paulette Senior

President and CEO,

Canadian Women’s Foundation, and;

Akela Peoples

CEO,

Mental Health Research Canada