With Chris Bail, Founding Director of the Polarization Lab. The fact that social media platforms draw out and reward anti-social, polarizing behaviour goes hand-in-hand with the gendered hate and abuse so common to digital interactions. We can’t fix one without fixing the other.

Nor can we ignore what social media does for us psychologically and socially. We use these platforms to build our personal identities. We use them to find community and a sense of belonging. This doesn’t have to be a bad thing. It’s often a good thing. But it gets dangerous when platforms reward attacking and hurtful behaviour, when they encourage the targeting of vulnerable people, and when they make it easy to exert power over those with less power.

In that sense, it’s easy to see why women, girls, and gender-diverse people, especially those who face multiple barriers, are so unsafe in digital spaces. Digital spaces reinforce and amplify the unbalanced power and abuse we know too well in our day-to-day lives.

There’s a glimmer of hope: digital spaces are ultimately human built. The fact that they’re like this is not inevitable and it’s not unchangeable.

Over coming months, we’re delving into this with leading experts and content creators, releasing in-depth episodes every single week. We talk about the problem and what we can do to change it. We offer practical tips to help you in your digital life, and we talk about what it means to “take back the tech” for all of us.

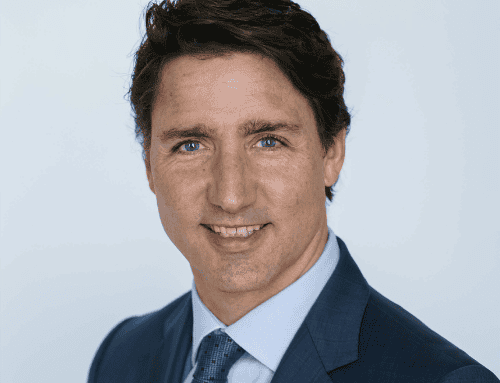

We’re joined by Chris Bail, Professor of Sociology and Public Policy at Duke University, where he directs the Polarization Lab. He studies political tribalism, extremism, and social psychology using data from social media and tools from the emerging field of computational social science. He is the author of Breaking the Social Media Prism: How to Make our Platforms Less Polarizing. A Guggenheim Fellow and Carnegie Fellow, Chris’s research appears in leading publications such as Science, the American Journal of Public Health, and New York Times. He appeared on NBC Nightly News, CBS News, BBC, and CNN. His research has been covered by Wired, The Atlantic, Scientific American, and more. He regularly lectures to government, business, and the non-profit sector and consults with social media platforms struggling to combat polarization. He serves on the Advisory Committee to the National Science Foundation’s Social Behavioral and Economic Sciences Directorate and helped create Duke’s Interdisciplinary Data Science Program. Chris received his PhD from Harvard University in 2011.

Transcript

00:00:03 Chris

The best way to describe what social media does and why it polarizes us is that it bends perception from reality at a fundamental level.

00:00:13 Andrea

Countering gendered digital hate and violence means addressing the polarizing distortions of digital life. How do we do that?

I’m Andrea Gunraj from the Canadian Women’s Foundation.

Welcome to Alright, Now What? a podcast from the Canadian Women’s Foundation. We put an intersectional feminist lens on stories that make you wonder, “why is this still happening?” We explore systemic routes and strategies for change that will move us closer to the goal of gender justice.

The work of the Canadian Women’s Foundation and our partners takes place on traditional First Nations, Métis and Inuit territories. We are grateful for the opportunity to meet and work on this land. However, we recognize that land acknowledgements are not enough. We need to pursue truth, reconciliation, decolonization, and allyship in an ongoing effort to make right with all our relations.

00:01:09 Andrea

Whether you’re on social media, streaming platforms, dating, messaging and meeting apps, or on game sites, if you’re a woman, girl, Two Spirit, trans, or non-binary person, you’re at greater risk of hate, harassment, and violence.

The fact that social media platforms seem to draw out and reward anti-social, polarizing behaviour goes hand-in-hand with the gendered hate and abuse so common to digital interactions. We can’t fix one without fixing the other.

Nor can we ignore what social media does for us psychologically and socially. We use these platforms to build our personal identities. We use them to keep and find community and a sense of belonging and clout. This doesn’t have to be a bad thing in and of itself. It’s often a good thing. But it gets dangerous when platforms reward attacking and hurtful behaviour, when they encourage the targeting of vulnerable people, and when they make it easy to exert power over those with less power.

In that sense, it’s easy to see why women, girls, and gender-diverse people, especially those who face multiple barriers, are so unsafe in digital spaces. Digital spaces reinforce and amplify the unbalanced power and abuse we know too well in our day-to-day lives.

There is a glimmer of hope here: this is a human dynamic. Digital spaces are ultimately human built. The fact that they’re like this is not inevitable and it’s not unchangeable.

Over coming months, we’re delving into this with leading experts and content creators, releasing in-depth episodes every week. We talk about the problem and what we can do to change it. We offer practical tips to help you in your digital life, and we talk about what it means to “take back the tech” for all of us.

Chris Bail, Professor of Sociology and Public Policy at Duke University, joins us now. He directs the Polarization Lab. A Guggenheim and Carnegie Fellow, Chris studies political extremism on social media using tools from the emerging field of computational social science. He’s author of Breaking the Social Media Prism: How to Make our Platforms Less Polarizing.

00:03:22 Chris

I lead an interdisciplinary research team called the Polarization Lab, and our mission is to both do high quality research on the key drivers of antisocial behaviour on social media. So, this is everything from spreading misinformation to polarizing behaviour and harassment. But also, to try to develop new technological solutions to address these problems. And you know, I’ve been working on this for about 15 years now, 10 to 15 years.

My interest in this space originated for a few different reasons. Living in the United States, it’s a pretty polarized place and sort of growing up with social media. I’m old enough to remember life without social media, so it’s sort of inevitable that people in our generation ask questions about how technology is shaping politics and online behaviour and harassment and all these things. And I’m also just sort of a lifelong interest and exposure to conflict in other parts of the world far outside the US, and I think that that also really stimulated my interest and appreciation for the urgency of solving these problems.

00:04:27 Andrea

Social media polarization seems to be a huge and growing problem. What have you learned about how and why it happens?

00:04:35 Chris

Polarization is a complex, multifaceted problem. In the US, and you know, we need more research outside the US. And I won’t be able to explain exactly how polarization emerges in all contexts, but in the US, it seems to be a combination of a few different factors. There’s a historical story about how the political parties in the US sort of drifted to extremes, particularly the Republican Party, long before social media was even around. Cable news stations, which people like to say they could afford to offend, because unlike the large networks like you know, your Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, you know, if they say something extreme some a place like CBC could get in trouble, right? But a small little niche organization like a Fox News in the US, especially early on, you know, they attracted audiences by saying crazy stuff. So, you know, that’s 1990s. And then up through the 2000s, we start to see, you know, protean forms of social media, but we don’t really see wide scale adoption of social media until probably the end of that decade. So, long before social media came around, there were lots of other factors driving polarization, probably inequality, social isolation and all sorts of other stuff.

And a lot of people want to ask the question, did social media cause polarization or you know, other forms of harassment, and I find it pretty much impossible to answer that question, right? We can’t disentangle the role of social media from so many other factors. But I think what we can do is realize that social media has created some changes which likely didn’t make anything better.

I like to say that the thing that makes us human is that we care so much about what other people think about us. Compared to other creatures, right, that’s what makes us unusual. And you know, from birth we have an instinct to sort of scan our social environments, trying to figure out what other people think about us, and then we tend to cultivate identities that make us feel better about ourselves, right? And we jettison those that don’t.

Before social media, you know, we’re all just kind of walking around in our communities. You know, we’re getting feedback from each other or, you know, maybe you see someone smile or you know, you get a head nod or something that sort of gives you some subtle cues about which identity is working for you.

Fast forward to social media and things are just profoundly different, right? I can be anything to anyone. I can be on many platforms, fully anonymous. I can be… I can stretch the truth. I can bend the truth. And so, at a fundamental level, the way that we can experiment on our identities has changed. You know we’re no longer constrained to what we look like in person, right? Like nobody who meets me in person is going to think like I’m a talented break dancer, right? It’s just like I’m a pretty goofy person. The second you made me realize that, right? But online, like, I could pretend to be, right?

The other way things have changed. Platforms interact with this human tendency in ways that I think are pretty unproductive. So, for example, we have follower accounts, we have like buttons. We have all this infrastructure that gives us the sense that we have a heightened ability to figure out what other people think about us and that’s what, for me, that’s what we’re addicted to with social media. I ‘s this tool that we can quickly use to figure out what other people think of us.

But of course, if we rely upon those things – follower counts, like, you know, like counts, all these things – we’re getting a very distorted picture of what people actually think about us. And that’s why I called my book Breaking the Social Media Prism, because I think the best way to describe what social media does and why it polarizes us is that it bends perception from reality at a fundamental level.

00:08:32 Andrea

We’ve been talking a lot about the structural issues behind digital hate and harassment. I see that you get into the psychological level in your research. It gets personal and we can see ourselves in it. It triggers another level of curiosity about what’s going on.

00:08:48 Chris

One of the interesting things about the research my colleagues and I have been able to do is, in addition to studying people using what you might call digital exhaust – the little pieces of information they leave behind on social media sites that researchers like me can scrape using computer programs and, you know, try to make sense of – but then also we talked to a lot of these people. You know, we actually, we studied them, they participated in experiments with us, but we also talked to them.

I think the best way to answer your question is to give the example of a guy who we met, who I’ll called Ray to protect his identity. Pretty interesting. We first start talking to him, he’s like a pretty likable guy, you know, he’s going out of his way to say you know, “Hey, I tried to get along with everyone”. You know, carefully says, “I don’t care about race. People who talk about politics all the time sort of bother me, you know? But you know, overall, I just like to connect to people.” So, that’s relatively pleasant conversation with this guy and then we go to look at his social media data, which we had obtained through a survey firm that recruited him to participate in our research. And this was the biggest troll I’ve ever seen in 10 years of studying incivility on social media.

So, it’s like, immediately, a bunch of questions came up. You know, one – did we mess up the data merge somehow? Is this even the same person? Turns out, yes. We were able to, through some digital forensics, determine this is the same guy. His newsfeed is just post, after post, after post, of meticulously photoshopped memes depicting Liberal Democrats, especially women like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, or Nancy Pelosi – two prominent politicians here in the US. You know, in the most vile, you know, reprehensible ways. And so, it’s like every night, this guy is changing from Dr. Jekyll into Mr. Hyde.

And here’s where I think the gap between perception and reality is so important. When we encounter someone online, we just see, you know, one side of their persona. And if you think about the incentive structure of social media, what do you get likes for? What do you get follows for? And why do you go there in the first place, right? We don’t talk enough about the motivations of social media users and when we got to know more about this guy Ray, we discovered, you know, he’s a middle-aged guy, he’s not married, he lives with his mom. You know, he’s got sort of a pretty sad life. Doesn’t have a lot of friends. He, like all of us, sort of has a quest for social status. You know, we want to belong. We want to fit in. And so, he starts to explore using platforms like Twitter. And this is many years ago. You know, he starts to try out some content and he’s not getting, you know, many likes for his first few posts. And then he starts talking about Barack Obama and then he, you know, says something a little more extreme and more extreme. Each time he gets more extreme, he gets more like … You know, I can tell you, having looked at those posts, that the people liking his posts were some of the most extreme people on the Internet.

And the problem actually is that the most extreme people on the Internet are also the most active users on the Internet. And so that means that many of us are going to profoundly exaggerate how extreme everyone is, just because these extreme people are hyperactive. But setting that aside for a minute, we can understand raised behaviour, I think, as you know, a kind of social feedback and reinforcement, right? Like he gets what he needs – a sense of status and belonging – from this group of people that he’s never going to meet in person that he thinks you know is a vast and important group of people who are validating his views, right? You know, the motivation here is again, what motivates all of us. Like we want to be loved, we want to belong, right? Some people, like this guy Ray, need social media to get that validation. Most, or maybe even many of us, don’t. We get our validation in offline settings through our jobs or through our, you know relationships.

So, we really can’t abstract from the bigger picture here. You know, and especially in the area that you are focused on, right. Who are these people? Is a question I think so many of us are asking. I don’t think they’re all like this guy, Ray. But I think many of them are.

Understanding where they’re coming from – I’m not saying we should sympathize with people who engage in hateful, abusive behaviour. Quite the contrary, I think we absolutely need to do more about this, but I think effective interventions will require understanding their motivations.

00:13:25 Andrea

You probably don’t get surprised by much anymore, but I’ll ask you what I’ve asked other researchers: does anything surprise you about what you’ve learned?

00:13:34 Chris

I think I put on a good ask, to be fair. You know, like one of the things you mentioned – curiosity. And I really appreciate that comment about the book because I do think that’s something all of us could use more of. You know, if we approach these questions with outrage, right, we’re not going to solve them very effectively. In fact, we might make things worse if we attack trolls, right. Like there’s a fair amount of evidence as to why that happens. You know, but curiosity. Yeah, like, pull back the curtain a little bit. Like, who is this person, you know?

In doing these interviews, you know I often, you know, concluded these people were much more complex than I thought they were. So, another good example in the introduction to my book, I talk about a guy we call Dave. If you saw him on Twitter, you would think he is just a crude racist who is engaged in an argument about white supremacists marching on a college campus near where he lives.

That’s what I thought. You know, I looked at this post. I’m like, wow, this guy just does not seem like a like a particularly great, you know, great guy. And again, we talked to him, which requires a little bit of, you know, curiosity. Maybe, I don’t know if we can say, you know, say it’s brave, but like actually trying to understand how the guy works.

Turns out you know, he’s half Puerto Rican. He grew up experiencing racism as a child. He was motivated to engage in this argument about white supremacism because he worries that the liberal media is sort of turning racial problems into race problems in a way that is unwarranted and that masks the real type of harassment and humiliation that he experienced. So, you know there’s some complexity there.

And I was humbled by some of the interactions I had with social media users. You know, I was sitting there being like, well it’s easy for me to spot misinformation on Twitter because I’m, you know, I’m an educated person. But the thing that drives extremists crazy, I think, is when they perceive that everyone, especially academics like me or other kinds of activists have a monopoly on the truth. You know that we get to define what the problems are, right? It’s a debatable point. I think we do a pretty good job on a whole, but that perception again, we’ve been talking about the gap between perception and reality.

The perception that we are subtly controlling the contours of the conversation in a way that doesn’t allow people to participate is the thing that enrages, and I think even in some cases, radicalizes people – makes them vulnerable to things like conspiracy theories and to kind of gang dynamics that we see in so many Internet communities.

00:16:09 Andrea

What I take from your work is that the relatable human search for respect and belonging has gone digital, and especially in social media spaces, set up the way they are, that has its challenges.

00:16:20 Chris

Yeah. I mean, I think, yeah fundamentally, everybody wants to be respected.

Now, you know, like, let’s look at the current situation with, say, Twitter, you know? Like I think you and I probably both agree, it’s a pretty, pretty hot mess. It’s not as if the solution is just: tear down the guardrails, let’s have a genuine competition of ideas. That just misunderstands what social media is and why people use it. The number of people who go on a place like Twitter to have a productive rational conversation, about, say, the minimum wage, is infinitesimally small part of the population.

Most people are on there to entertain themselves, right? They’re talking about sports or video games. They don’t even care about or maybe even know in many cases, about policies about the minimum wage. Other people are just out there to win status, you know, to gain, again, a sense of belonging and stuff like that. If people are out to gain a sense of belonging, this does not make them pro social creatures who are going to try to naturally reach consensus, right. We’re humans. We’re sort of wired in team dynamics and group dynamics and so of course, you know we sort of divide ourselves into, you know, rival communities and win status primarily by attacking the other side.

Nobody is going on there to try to change someone’s mind. Like everybody knows it’s futile to try to change someone’s mind on social media, right? It’s all performance, it’s all theatrics, it’s all playing for your side and trying to win the argument. It doesn’t have to be that way, right? Like, I think one of the things that I’m particularly passionate about is like how do we reverse floors? Particularly for people from marginalized groups – right, disempowered people – social media is almost certainly a net negative.

When you start to look forward, can you change the incentive structure of social media, I think. Instead of making social media about winning status and engagement, no matter what the consequence is, we can better define what type of engagement we want. You know, there’s a lot of talk about algorithms and how the algorithms are radicalizing people. And you know, there’s a lot of complicated research on that topic. But I think one thing that a lot of researchers are great about is that you know most of these social media platforms, they order information in our newsfeed or for your “for you page” by putting the stuff near the top that got the most engagement from other people. Regardless of whether it’s engaging right. So, to your point, you know, this post is getting a lot of engagement, both positive and negative, and it’s getting boosted and then more people are getting pissed off and more people are getting pissed off, right.

The structure of social media platforms is designed to promote viral advertising, right? You want to get many eyeballs on something as possible. Just keep people looking at it. You know, we do need a way to keep social media engaging, so like if you want, you know, if you want to bore yourself to death, try setting your social media news feed to chronological order – if the platform will allow it.

I don’t think anybody really wants that in this day and age where we’re so used to information being curated for us. But the question is, is there something better than this engagement-based virality model to capture our eyeballs? And here’s what I think. I think what we need to do is reward behaviour that is consensus building. Build that into these algorithms. So, instead of rising to the top of the news feed for taking down someone who you know who has a different political view – which is what’s going on right now – boost the people whose messages are getting positive feedback from lots of different types of people. Could be, in the US, Republicans and Democrats, could be men and women, could be young people and old.

And in this way, you’re doing a few things. One, you are optimizing for consensus, right? You want to show people stuff that’s useful, positive, and so on and so forth. But two, you’re making the platform a much less fun place for trolls, people who are harassing each other, to play. If you are going to drift to the bottom of the news feed every time you uncivilly attack someone, then you’re probably not going to use that platform.

00:20:29 Andrea

You speak primarily about social media in the United States. I do wonder if you see anything particular about the situation in Canada and the rest of the world.

00:20:37 Chris

Well, you know the old saying: when the US gets a cough, the rest of the world gets pneumonia, in terms of the economy, right? Like I do worry. One of you know my country’s chief exports lately has been polarizing social media and the good news is there’s variation here.

There’s a very interesting study. Recently came out in the journal Nature Human Behaviour. And this is a group of European researchers. And they said, “OK, you know what, we’ve been studying social media and politics, extremism, things like this for about 10-15 years now and there’s hundreds of studies. Let’s step back and try to do some accounting and let’s, especially, let’s track things around the world.” And so, they looked at a number of different things. So, they looked at studies that looked at things like, you know, does social media spread misinformation, does social media create polarization, does it reduce trust? All these kinds of things.

And then they looked at whether the findings of the study suggested social media was primarily positive or primarily negative, and then they also measured where the study took place. And the striking finding from the study was that in the US and Western Europe and Canada, the net effect of social media was mostly negative. It’s making things worse.

Interestingly though, for the rest of the world, it was basically the opposite, and this was shocking. You know, we all hear about Facebook being accused of facilitating genocide in places like Myanmar. And so we think that, oh, this has got to be, you know, this has got to be just even worse than other places. But so far what the scholarly record is showing is exactly the opposite.

And so I think, it begs really important questions about how social media interacts with existing political structures. You know, Canada, like the US, has a relatively bipolar, Manichean kind of political structure. In many ways, it’s politically very similar to the US. So it could be that in these two-party systems, social media is sort of an accelerant. You know, gas on the fire. And in other places like for example, there isn’t a strong civil society, there isn’t a strong, you know, media presence apart from a state media, you know, it makes perfect sense that social media could enable new kinds of connection – enable people to gain access to new kinds of information, right, to partner with new people, to engage in microlending.

Like there’s so many positives and so what I worry about in the big picture is that as we focus on the negatives of social media – and we absolutely should like there’s many, many bad things going on – but we also don’t want to throw the baby out with the bathwater, right? You know, like a lot of people want to say we should stop using social media. It’s just not going to happen. Social media is embedded in the fabric of pretty much every part of our lives.

So, the question for me is not, do we try to get rid of social media? But how do we make it better and how do we optimize for positive pro social consensus building behaviour. If there’s some skeptics in your audience you might be thinking like, “What is this, you know, do people really want positive stuff?” Turns out, yes. You know, surveys of the US population, if you ask them why does stuff go viral? They’ll say, “Oh, it’s because of, you know, people saying hateful negative stuff”. Then they’ll say, what would you like to make things go viral? And they say, “I would like useful stuff. I would like information. You know, I would like high quality information. I would like to hear stories about how people came together to fix things, you know, and yes, cute cats”, which by the way is consensus, right.

It’s a complicated path forward. It’s going to be different in different places, I think Canada will, yes be very similar to the US in many ways, especially given our proximity, but also different. You know the multiculturalism, the different traditions. You know these are naturally going to create a different environment.

00:24:22 Andrea

What can we as individual users do to make social media less polarizing and harmful to ourselves and others?

00:24:29 Chris

In addition to challenging the platforms to change – which we absolutely need, we need to criticize them, they need to be pushed in many, many, many ways, including by government – we also need to understand how our own behaviour contributes to the bigger picture. Far from saying, let’s blame the victims here, right. But I do think when we intervene, we need to sort of adopt a first, do no harm kind of perspective. For example, if we see some content we don’t like, you know we immediately jump into the comments and say, “How can you possibly think this? This is, this is wrong. You know you’re…” It’s usually a lot less friendly than that right, but we get angry.

We used to say in the 1980s-1990s, when we were talking about misbehaviour among large corporations, we would talk about voting with your wallet or your pocketbook. As individuals, we don’t have much power, except for what we buy. And now for my money, it’s not what we buy, but what we like, you know how we engage. So, do I doom scroll for another two hours and share my angry opinion with someone for another two hours tonight? Or do I just ignore it? I don’t think ignoring it is a great solution either, right? Because that allows it to go unchallenged in some sense. But if we remember that our actions have consequences, they will actually make more people look at this thing that we’re trying to discredit, you know, we might think twice and we might pick our battles a little more carefully. So, I think like being a little bit more reflective about how our behaviour contributes to the bigger picture and you know we talk about supporting each other and you know we don’t want to… That is a consequence of inaction too, right. People might feel unsupported.

But maybe that’s an opportunity to jump to DM, right? And just say, “Hey, just so you know, I don’t accept… I find this thing that someone did to you reprehensible. I don’t want to support it by replying in public, but just so you know I got your back.” Again, you know we have to get creative. We don’t get to control, you know, the algorithm.

It’s not an easy solution. I don’t think there’s any single solution, but understanding how you know we’re voting with our like buttons; we’re voting with our comments, is a key part.

We can also control to some extent what type of information we expose ourselves to. So, for example, earlier I was talking about bridging-based algorithms that would reward consensus. We actually built a tool that a bot that would spread this type of content and we put it out on Twitter until Elon Musk shut down all access to Twitter’s data among researchers like me. But for a short time, you know, you could follow this bot and try it out. You know, while you’re waiting for platform to change, you can change them yourselves.

And I predict, you know, we’re going to see a broad decentralization of social media. More and more splintering into smaller and smaller platforms. In order to compete with each other, these platforms are going to have to give us more options, right? You know, more features. And one of the ones I predict we’ll see is more and more control at the user level, right? For what your experience is like. People talk about algorithmic choice and something like Bluesky and Twitter and you know Threads being part of the Fediverse, which is the decentralized platform that hosts platforms like Mastodon, right? So, I think this is where we’re headed and you know, maybe those choices will allow us to have more control over this, too.

On polarizationlab.com, we have a suite of free tools and apps, or what we like to call middleware. So, these are sort of like apps and bots and other sorts of things that you can use in tandem with social media to try to improve your experience.

00:28:04 Andrea

Alright, now what? Check out the tools and research at the polarization lab by visiting polarizationlab.com.

Get the facts on gendered digital hate, harassment, and abuse by visiting our fact page on canadianwomen.org.

While you’re there, read about our new Feminist Creator Prize to uplift feminist digital creators advocating for gender justice, safety, and freedom from harm.

Did this episode help you? Did you learn anything new? We want to know! Please visit this episode’s show notes to fill out our brief listener survey. You’ll be entered to win a special prize pack.

This series of podcast episodes has been made possible in part by the Government of Canada.

Please listen, subscribe, rate, and review this podcast. If you appreciate this content, please consider becoming a monthly donor to the Canadian Women’s Foundation. People like you will make the goal of gender justice a reality. Visit canadianwomen.org to give today and thank you for your tireless support.